Natural Rate of Unemployment

What is the Natural Rate of Unemployment?

- Marketing, Advertising, Sales & PR

- Accounting, Taxation, and Reporting

- Professionalism & Career Development

-

Law, Transactions, & Risk Management

Government, Legal System, Administrative Law, & Constitutional Law Legal Disputes - Civil & Criminal Law Agency Law HR, Employment, Labor, & Discrimination Business Entities, Corporate Governance & Ownership Business Transactions, Antitrust, & Securities Law Real Estate, Personal, & Intellectual Property Commercial Law: Contract, Payments, Security Interests, & Bankruptcy Consumer Protection Insurance & Risk Management Immigration Law Environmental Protection Law Inheritance, Estates, and Trusts

- Business Management & Operations

- Economics, Finance, & Analytics

What is the Natural Rate of Unemployment?

Cyclical unemployment explains why unemployment rises during a recession and falls during an economic expansion, but what explains the remaining level of unemployment even in good economic times? Why is the unemployment rate never zero? Even when the U.S. economy is growing strongly, the unemployment rate only rarely dips as low as 4%. Moreover, the discussion earlier in this chapter pointed out that unemployment rates in many European countries like Italy, France, and Germany have often been remarkably high at various times in the last few decades. Why does some level of unemployment persist even when economies are growing strongly? Why are unemployment rates continually higher in certain economies, through good economic years and bad? Economists have a term to describe the remaining level of unemployment that occurs even when the economy is healthy: they call it the natural rate of unemployment.

The natural rate of unemployment is not “natural” in the sense that water freezes at 32 degrees Fahrenheit or boils at 212 degrees Fahrenheit. It is not a physical and unchanging law of nature. Instead, it is only the “natural” rate because it is the unemployment rate that would result from the combination of economic, social, and political factors that exist at a time—assuming the economy was neither booming nor in recession. These forces include the usual pattern of companies expanding and contracting their workforces in a dynamic economy, social and economic forces that affect the labor market, or public policies that affect either the eagerness of people to work or the willingness of businesses to hire. Let’s discuss these factors in more detail.

How Does the Natural Unemployment Rate Related to GDP?

The natural unemployment rate is related to two other important concepts: full employment and potential real GDP. Economists consider the economy to be at full employment when the actual unemployment rate is equal to the natural unemployment rate. When the economy is at full employment, real GDP is equal to potential real GDP. By contrast, when the economy is below full employment, the unemployment rate is greater than the natural unemployment rate and real GDP is less than potential. Finally, when the economy is above full employment, then the unemployment rate is less than the natural unemployment rate and real GDP is greater than potential. Operating above potential is only possible for a short while, since it is analogous to all workers working overtime.

How Does Public Policy Relate to the Natural Rate of Unemployment?

Public policy can also have a powerful effect on the natural rate of unemployment. On the supply side of the labor market, public policies to assist the unemployed can affect how eager people are to find work. For example, if a worker who loses a job is guaranteed a generous package of unemployment insurance, welfare benefits, food stamps, and government medical benefits, then the opportunity cost of unemployment is lower and that worker will be less eager to seek a new job.

What seems to matter most is not just the amount of these benefits, but how long they last. A society that provides generous help for the unemployed that cuts off after, say, six months, may provide less of an incentive for unemployment than a society that provides less generous help that lasts for several years. Conversely, government assistance for job search or retraining can in some cases encourage people back to work sooner.

On the demand side of the labor market, government rules, social institutions, and the presence of unions can affect the willingness of firms to hire. For example, if a government makes it hard for businesses to start up or to expand, by wrapping new businesses in bureaucratic red tape, then businesses will become more discouraged about hiring. Government regulations can make it harder to start a business by requiring that a new business obtain many permits and pay many fees, or by restricting the types and quality of products that a company can sell. Other government regulations, like zoning laws, may limit where companies can conduct business, or whether businesses are allowed to be open during evenings or on Sunday.

Whatever defenses may be offered for such laws in terms of social value—like the value some Christians place on not working on Sunday, or Orthodox Jews or highly observant Muslims on Saturday—these kinds of restrictions impose a barrier between some willing workers and other willing employers, and thus contribute to a higher natural rate of unemployment. Similarly, if government makes it difficult to fire or lay off workers, businesses may react by trying not to hire more workers than strictly necessary—since laying these workers off would be costly and difficult. High minimum wages may discourage businesses from hiring low-skill workers. Government rules may encourage and support powerful unions, which can then push up wages for union workers, but at a cost of discouraging businesses from hiring those workers.

Wages, Productivity, and the Natural Rate of Unemployment

Unexpected shifts in productivity can have a powerful effect on the natural rate of unemployment. Over time, workers' productivity determines the level of wages in an economy. After all, if a business paid workers more than could be justified by their productivity, the business will ultimately lose money and go bankrupt. Conversely, if a business tries to pay workers less than their productivity then, in a competitive labor market, other businesses will find it worthwhile to hire away those workers and pay them more.

However, adjustments of wages to productivity levels will not happen quickly or smoothly. Employers typically review wages only once or twice a year. In many modern jobs, it is difficult to measure productivity at the individual level. For example, how precisely would one measure the quantity produced by an accountant who is one of many people working in the tax department of a large corporation? Because productivity is difficult to observe, employers often determine wage increases based on recent experience with productivity. If productivity has been rising at, say, 2% per year, then wages rise at that level as well. However, when productivity changes unexpectedly, it can affect the natural rate of unemployment for a time.

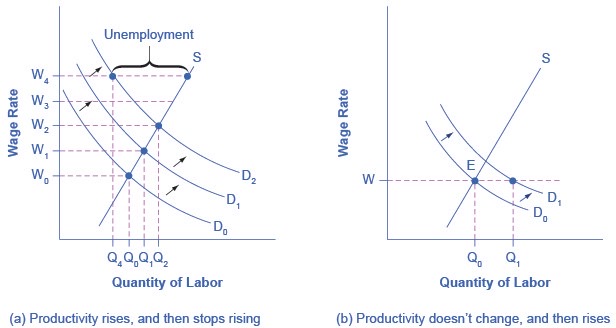

The below figure illustrates the situation where the demand for labor—that is, the quantity of labor that business is willing to hire at any given wage—has been shifting out a little each year because of rising productivity, from D0 to D1 to D2. As a result, equilibrium wages have been rising each year from W0 to W1 to W2. However, when productivity unexpectedly slows down, the pattern of wage increases does not adjust right away. Wages keep rising each year from W2 to W3 to W4, but the demand for labor is no longer shifting up. A gap opens where the quantity of labor supplied at wage level W4 is greater than the quantity demanded. The natural rate of unemployment rises. In the aftermath of this unexpectedly low productivity in the 1970s, the national unemployment rate did not fall below 7% from May, 1980 until 1986. Over time, the rise in wages will adjust to match the slower gains in productivity, and the unemployment rate will ease back down, but this process may take years.

(a) Productivity is rising, increasing the demand for labor. Employers and workers become used to the pattern of wage increases. Then productivity suddenly stops increasing. However, the expectations of employers and workers for wage increases do not shift immediately, so wages keep rising as before. However, the demand for labor has not increased, so at wage W4, unemployment exists where the quantity supplied of labor exceeds the quantity demanded. (b) The rate of productivity increase has been zero for a time, so employers and workers have come to accept the equilibrium wage level (W). Then productivity increases unexpectedly, shifting demand for labor from D0 to D1. At the wage (W), this means that the quantity demanded of labor exceeds the quantity supplied, and with job offers plentiful, the unemployment rate will be low.

The economic lesson of the story is easier to see graphically, and say that productivity had not been increasing at all in earlier years, so the intersection of the labor market was at point E, where the demand curve for labor (D0) intersects the supply curve for labor. As a result, real wages were not increasing. Now, productivity jumps upward, which shifts the demand for labor out to the right, from D0 to D1. At least for a time, however, wages are still set according to the earlier expectations of no productivity growth, so wages do not rise. The result is that at the prevailing wage level (W), the quantity of labor demanded (Qd) will for a time exceed the quantity of labor supplied (Qs), and unemployment will be very low - actually below the natural level of unemployment for a time. This pattern of unexpectedly high productivity helps to explain why the unemployment rate stayed below 4.5%—quite a low level by historical standards—from 1998 until after the U.S. economy had entered a recession in 2001.

Levels of unemployment will tend to be somewhat higher on average when productivity is unexpectedly low, and conversely, will tend to be somewhat lower on average when productivity is unexpectedly high. However, over time, wages do eventually adjust to reflect productivity levels.

Related Topics

- What is the US Labor Force?

- Out of the Labor Force

- Labor Force Participation Rate

- Establishment Payroll Survey

- Bureau of Labor Statistics

- Unemployment

- Underemployed

- Full Employment Equilibrium

- Okun's Law

- Issues with Measuring Unemployment

- Sticky Wage Theory (Economics)

- Implicit Contract Theory of Wages

- Efficient Wage Theory

- Adverse Selection of Wage Cuts Argument

- The Insider-Outsider Model

- Relative Wage Coordination Argument

- Natural Rate of Unemployment

- Frictional Unemployment

- Structural Unemployment

- Labor Productivity - Explained

- Okun's Law

- How does U.S. unemployment insurance work?

- National Average Wage Index

- Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey

- Labor Surplus Area - Explained

- Lump of Labor Fallacy - Explained

- Bureau of Labor Statistics

- ADP National Employment Survey

- Labor Theory of Value - Explained

- Wage Elasticity of Labor Supply